We, the youngsters, spending our carefree summers in Keurkune, were the heralds of the generation known in the West as baby boomers born on and onward 1946. By the time we started being aware and know those around us, we had already learned that Mukhtar Baboug and his wife Anna Naner had lost their only child during the Genocide. After their return, Mukhtar Baboug had embarked on search trips tracking back their caravan route into the interior of Syria looking for the son he had lost. George Apelian narrates Mukhtar Nshan’s poignant search for his lost son Khachig in his “Martyrdom for Life” Armenian book.

V.H. Apelian's Blog

Tuesday, December 12, 2017

Unforgettable Mukhtar Nshan

We, the youngsters, spending our carefree summers in Keurkune, were the heralds of the generation known in the West as baby boomers born on and onward 1946. By the time we started being aware and know those around us, we had already learned that Mukhtar Baboug and his wife Anna Naner had lost their only child during the Genocide. After their return, Mukhtar Baboug had embarked on search trips tracking back their caravan route into the interior of Syria looking for the son he had lost. George Apelian narrates Mukhtar Nshan’s poignant search for his lost son Khachig in his “Martyrdom for Life” Armenian book.

Monday, December 4, 2017

The Case for not Closing Armenian Nursing Home

Saturday, December 2, 2017

Խաչակիրը

Ճորճ Ազատ Աբէլեան, (1945 - 2008)

|

| Sitting L to R: Veronica (Shammas) Apelian, Julia (Boyadjian) Shammas, Nofer Apelian. Standing L to R: Vartouhie, Araxie, Ashod, George, Hratch, Hasmig Apelian. |

Այսպէս Ճորճը բնակեցաւ Քեսապ, Հալէպ, Պէյրութ, Լոս Անճելոս. բայց միշտ ապրեցաւ բիւրեղացած իր հայ ներաշխարհէն ներս: Չեմ գիտէր բնութեան ո՞ր դասաւորումը այսքան հայրինասիրութիւն կուտակած էր այս տղուն հոգիէն ներս, չըսելու համար հայրենապաշտութեամբ բեռնաւորած էր զինք, որպէս խաչ մը, որ տառացիօրէն ուսամբարձ շալկեց Ապրիլ 24-ին, 1972-ի հաւաքական հետիոտն ուխտագնացութեան ընթացքին, Անթիլիասի վանքէն դէպի Պիքֆայայի բարձունքին վրայ գտնուող Մեծ Եղեռնի յուշարձանը: Հայաստանի անկախութենէն ետք կրկին անգամ կատարեց խաչակրութիւն մը դէպի Գարիգին Նժդեհի շիրիմը որպէս ուխտագրացութիւն:

Saturday, November 25, 2017

Ara Lezk, the Village Named After a Legend.

|

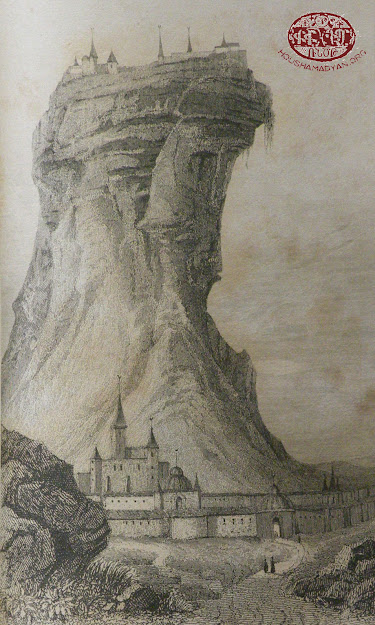

| Gravure: The Lezk (current Kalecik) village (Source: Jean Marie Chopin, César Famin, Eugène Boré, L'univers, vol. 2, 1838) (Houshamadyan) |

Saturday, November 18, 2017

Simon Vratsian’s Intuition: Vartan Gregorian and Richard Hovannisian

Richard Hovanissian’s life was altogether different from Vartan Gregorian’s. Richard’s parents were financially well off. He was living the American dream of a first-post genocide generation Armenian American, who did not speak Armenian but was involved in Armenian affairs through his association with Armenian Youth Federation (AYF). He was also attending Berkeley where he had met a girl, in her first year of medical school, named Vartiter.

Right after his appointment as the principal of the Hamazgayin Nshan Palanjian Jemaran, where Vartan Gregorian was already a student, Vratsian arrived in San Francisco, in early 1952, touring the Armenian American communities for the cause of Armenian education. It is there that Richard Hovannisian attended his lecture and "afterward, approached the prime minister for a few words. Instead, he received the offer of a lifetime.” Mr. Vratsian suggested Richard should spend a year at the Jemaran to learn Armenian.

Three years later, on September 20, 1955, Richard arrived in Beirut. At the request of Mr. Vratsian, Antoine Keheyan, who taught English in Jemaran and was more known by his endearing moniker, “Sir” than his name, and medical student Hrayr Kabakian, met him at the airport. “At the first sight of that clumsy American,” wrote Garin about his grandfather, both “wondered what the prime minister has seen in him?” Incidentally, in time Hrayr Kabakian would emerge as a prominent A.R.F. leader.

During Richard’s study in Jemaran, Mr. Vratsian prophetically confided to Sir that Richard, whom he called Dikran, would one day serve Armenian history and to Richard, he noted that upon his return he would marry Vartiter, with whom Mr. Vratsian was corresponding and had written to her to alleviate her concern whether she would be doing the right thing, to which Vratsian had written to her that saluting the host country’s flag is one of respect and not necessarily a principled support of the country’s policies. The present days’ athletes should heed the advice of “the unofficial warden of Armenia Diaspora”, Mr. Simon Vratsian, according to Garine Hovanissian.

What drove Vratsian to suggest the eager young man Richard Hovannisian was, to spend time in Jemaran? His motive has long been buried with him. Why did Mr. Vratsian take Vartan, the young student from Iran, under his wings? That also is a mystery. “I have wondered during the past forty years”, wrote Vartan Gregorian, “why I was chosen by Mr. Vratsian to be ‘a pair of his eyes’, or his ‘eyeglasses’. Was it due to the fact that I was alone in Beirut? That I had no family obligations, and practically no social life, and hence could spend inordinate hours with him? That I was from Iran and spoke eastern Armenian, his maternal language? That he knew first hand that I wrote well? That he trusted me and knew that I would never divulge his confidences? That he wanted to help me survive and help educate me? Or was it perhaps that I reminded him occasionally of his late young son, who had died during the 1921 exodus of the anti-Bolshevik Armenians from Armenia to Iran? Maybe it was a combination of all these things.”

Vartan Gregorian surely and rightfully ponders to find an answer for his unique relationship with Mr. Vratsian. But it appears that there was more to it. All the possibilities Vartan lists could have been legitimate reasons for Mr. Vratsian to treat Vartan as a son but cannot possibly explain why the other young man, Richard Hovannisian, had also caught Mr. Vratsian’s attention. Mr. Vratsian had no real reasons to bestow upon Richard the same attention, care and concern he bestowed upon Vartan Gregorian because unlike Vartan, Richard came from America and was independently well off financially and did not need to accompany Mr. Vratsian accepting invitations for dinner just to help him fill up his belly.

The reasons must lay elsewhere. In both of them, the last prime minister of the First Republic of Armenia must have seen a potential to fill, in a way, his shoes as servants of the Armenian cause and Armenian history.

During their youth, Vartan Gregorian and Richard Hovannisian became Simon Vratsian’s protégés because Simon Vratsian must have intuitively noted a promising potential in both. The prominence of these two eminent individuals over the subsequent decades attests to Simon Vratsian’s intuitive understanding and appreciation of men, in the genderless sense of the word.

Vartan Gregorian remembers Hotel Lux

My father knew Vartan Gregorian and met him in the hotel when young Vartan had just arrived in Beirut from Iran on his way to continue his studies in Jemaran. Later on, as a student in Jemarant, Vartan lived with an Armenian family in a building next to the one we lived with my uncle's family in Zokak-El-Blat neighborhood in West Beirut, a few blocks away from Jemaran.

Hotel Lux was in downtown Beirut, not far from the parliament building. My father worked in the hotel when he left his native village Keurkune, Kessab in mid to late 1930;s when he was still in his later teens. Many Kessabtsi young men who left Kessab for Lebanon to escape possible conscription in the Turkish army had not learned any trade, as there were few such as tailoring the late Catholicos Karekin I/II had apprenticed in his youth. Thus, most of them worked as waiters and made their living by serving. Later on he ran that Armenian landmark inn, having added another floor, until its demise in 1976 because of the civil war in Lebanon.

The star marked on the picture above depicts the entrance of Hotel Lux, from Allenby Street but the main entrance of the hotel or rather the inn, was from the side street. Customers would be lifted to the upper floors of the building with an old-fashioned elevator, which constituted the famed Hotel Lux. Many in the close-knit Armenian community knew it as Tourig’s hotel. Mehran Tourigian had started it in late 1920’s or early 1930’s.

It would not surprise me that the white colored Volkswagen Beetle in the attached picture was actually the VW we owned. As to that corner store, it is from there that my father and later on I, bought the newly issued stamps for my Lebanese stamps collection, I still have. Along with the stamps, Chiclets gum, two in a small package and Cadbury chocolate bars, we fondly remember purchasing from that store. Regretfully downtown Lebanon became a casualty of the Lebanese civil war and was eventually bought by a company that the late PM Hariri owned or was its major stockholder. Visitors claim that t downtown Beirut has become an upper scale but a stale neighborhood as it has lost its charm.

The quotation below is from Vartan Gregorian's book "The Road to Home" (pages 65 and 66, 2003), where he describes his first day in Beirut having just arrived from Iran. I remember meeting him and his wife while we, as a family were taking a promenade along the coast, not far from the hotel. I remember Vartan and my parents speaking. Vartan was with his wife. That must have been when he returned to Beirut after receiving his PhD to teach and do research. I met Vartan the last time a few year's ago at the gala for the opening of the NAASR's new wing named after him. During the gala he stopped at each table. When I introduced myself, he remembered my father who had passed away in 2007.

This is how Vartan Gregorian's recalls his first day in Beirut ("The Road to Home", pages 65,66, 2003)

“Once in Beirut, I had stage fright. My Persian, Armenian, Turkish, even some Russian, proved insufficient as a means of communication. One of my companions on the IranAir flight came to my assistance. He helped me change Iranian rials to Lebanese pounds, negotiated the cab fare for me, and gave the driver the address of my destination in Beirut: Hotel Luxe. “Which one?” the driver asked. I said, “The one, the famous one. It is a well-known hotel.” The driver shook his head. “I know about the location,” he said, “but I have never heard about Hotel Lux.”

After a wild taxicab ride and an inquiry or two, the driver located the Hotel Luxe. It was in one of the busiest sections of the business district. Buried among a myriad of signs was a discreet, small sign indicating the exact location of the hotel. It was on the fifth floor of a building and was reached by a crude elevator. The hotel had six or seven rooms and a nice, large, airy rooftop terrace. The owner, Mr. Toorigian, and his family lived on the top floor. The kitchen served the family as well as the guests. It was a lively Armenian hotel. In the evenings, it served as a gathering place for several writers, or backgammon players, and discuss a variety of pressing national and international issues. It was sort of a modern-day salon.

The hotel’s rooms were occupied by visiting writers, teachers, and businessmen from Syria, Egypt, and Iraq. I was the first guest from Iran. I handed Mr. Maloyan’s letter to Mr. Toorigian. He extended a warm welcome and gave me a room, and asked me to join him, his family, and guests for breakfast, lunch, and dinner. The guests, all Armenians, spoke the western Armenian dialect. I spoke the eastern one, but we understood each other. My first night in Beirut was depressing. All of a sudden, I felt alone in the world. I was in a faraway place, in a strange city and strange hotel and bed, uprooted and transplanted to follow the unknown. I had neither friends nor acquaintances.

My first two weeks in Beirut were memorable even though I was alone and lonely. I found the city intoxicating. It was my first encounter with a foreign metropolis, a seaport, and ships. I experienced, for the first time, the distinctive smell of the sea, and the oppressive late summer heat and humidity of the city. This was offset by the clean air and gentle breeze of its beautiful nights.”

|

| On the veranda of Hotel Lux in 1963, your humble blogger Vahe H. Apelian |

Revised on 4/15/2021

Friday, November 17, 2017

ARMENIAN EVANGELICAL SCHOOLS OF CALIFORNIA, INC. The Founding of the First School

I came across these three unsighned typewritten and stapled pages in my mother’s archives. I could not trash them without reproducing it here. It narrates the chronology of the founding of the CHARLOTTE and ELISE MERDINIAN ARMENIAN EVANGELICAL SCHOOL and in doing so, illustrates the community-wide efforts that were vested in the founding of the school that had its start with thirteen students.

February, 1983