By Matheos Eblighatian

Translated by Vahe H. Apelian, Ph.D.

Edited by Jack Chelebian, M.D.

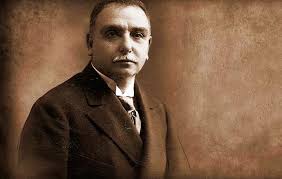

The same week the Minister of Justice issued a circular barring Krikor Zohrab from practicing law in the Ottoman courts.

From one day to the next, the man who was sprinting started walking on crutches. Henceforth, Zohrab could work only in the courts set by the embassies. He also could work as a legal consultant to lawyers of the Ottoman court. The ruling reduced his earning potential to a quarter of what it was. He was also afraid of the worst. It was the Hamidian era. Influential persons would disappear without a trace and no one would have the courage to inquire about them with government officials.

A free thinker like Zohrab, naturally, could not be fond of Turkey’s dictatorial regime. And when its heavy hand came down on his head, of course, he reacted. Zohrab started working with the Russian Embassy and was appointed the Embassy’s legal consultant. The Ambassador showed much interest in the plight of the Armenians. Zohrab, in turn, felt the need to do his best to put an end to Sultan Abdul Hamid’s anti-Armenian policies. Zohrab also went to Europe and under an assumed name wrote a book in French on that topic.

These uncertain and dangerous days came to an end. On July 10, 1908, for the second time, the Hamidian constitution was declared. The following year (1909), when Sultan Abdul Hamid was dethroned in early April, Zohrab and Halladjian were elected as Armenian community’s representatives (from Constantinople) in the Turkish Parliament. The same year, I was sent to a remote corner in Turkey called Yania as a judge and moved away from Istanbul when Zohrab was financially very well off. At the same time, new national and political horizons had opened in front of him. Only a gifted individual like him could meet the demands of his office as a parliamentarian.

After moving away from Istanbul until 1912-1913, I followed Zohrab’s activities through the Armenian newspapers and through Turkish newspapers as well. During that time Zohrab had also become a professor in the School of Law. The students would talk about him with admiration. Much like the other Armenian representative Bedros Hallajian, Zohrab had not become a member of the Ittihad party. The Ittihad party leaders admired him but yet were wary of him. Whenever Zohrab articulated about an issue in the parliament, he came across as an authority. Zohrab also shined in the Armenian community. It was not only because he was a member of the parliament. After all, Halajian was a member of the parliament as well. He championed liberal causes, against the conservatives, in the Armenian National Assembly. He was not a member of Armenian political parties and had no inclination to espouse socialist ideology. He had a powerful personality to be confined by any party ideology.

As I had noted earlier, during the time he was barred from practicing law in Ottoman courts, he had established a close relationship with the Russian Embassy promoting reformation to put an end to the oppression of the Armenian subjects in the interior of the country. He had his considerable input in the Patriarchate to address the grievances of the Armenians. Let us not forget that at that time the name was Ottoman and was not Turkey as it is now. The Armenians, the Turks, the Greeks, the Albanians and the Arabs were constituents of the country. Therefore every one needed to strive to achieve the common good in the country they were part of.

It is known nowadays that the Ottoman Constitution did not achieve that. Those who harbored illusions and hopes had their rude awakening when they read Hussein Jahid’s theory of “the dominant people”; according to which the rest of the constituents of the Ottoman society were subservient to the dominant Turks. The Turks were not content with monopolizing the country and the government but also resorted to oppressing and massacring the rest.

The Turks wanted the rest to think much like them but without granting the rest the rights and the privileges they enjoyed. We did not even have the right to keep the fruits of our own labor. A healthy, lively, robust and clever Armenian tradesman was not to their liking. For an Armenian to be wealthy was regarded as some sort of transgression. Establishing amicable relations with foreigners residing in the country was considered an unforgivable sin. Our socio-economic comfort provoked their envy. They considered us having a graceful wife or beautiful daughter were gifts we did not deserve. To top it all, they demanded that we respect them, remain loyal to their individual and national interests. Such was the reigning state of affairs before and after the 1909 Constitution. Naturally, the other ethnic groups did not feel a kinship with the Turks. A Greek parliamentarian at one time said that his relationship with the Ottoman government is like that of the Ottoman Bank’s relationship with the government, that is to say by name only. Zohrab (as an Armenian parliamentarian) likewise had a right for similar perspective, and could act accordingly. Consequently, the Turkish officials’ ceaseless efforts to convince the Armenian community to expect the implementation of reforms solely from the Ottoman government perspective, was futile. There are those among us who think that that we should have acted this way or that way and that it would have been more favorable for us to concede and get by. While we looked to foreign powers to bring about reformation to achieve a dignified life, our relations with the Ottoman government always remained lawful.

Right around this time, Krikor Zohrab wrote an article proposing that the prelates in the provinces be knowledgeable in jurisprudence to best represent the Armenian community to the government. While I appreciated the necessity for this, I had a better grasp of the reality. Consequently, I responded to Zohrab’s article noting that it is not likely that a person who has attained a law degree would choose to be a celibate priest. It is more realistic, I argued, that knowledgeable professionals be appointed as advisors to the prelates. I argued the same in the Armenian National Assembly when it came to appointing officials to the Patriarchate.

Naturally, this was not going to happen overnight. I mention it here to note that all we wanted from the Ottoman Government was securing our lives, honor, and properties through law. We all know it did not happen and in fact, nothing changed. Foreign nationals proposed laws to achieve these objectives. But the persons who were to enact and enforce the proposed laws were the Turkish ministers who chose what suited their sinister goals.

It is often told that Talaat Pasha got emotional and embraced Krikor Zohrab as they parted after socializing at the Circle D’Orient Club, but even Talaat knew the black fate that awaited Zohrab and Vartkes on the very next day. Consequently, some people conclude that Talaat was reluctant to endorse the destruction of his friend. The following day Zohrab and Vartkes were indeed apprehended and sent to face the military tribunal in Dikranagerd and on their way there, they were both killed.

I knew from reliable sources what Talaat said about Zohrab months after his martyrdom. Talaat claimed that after the declaration of war, the Russian Ambassador had left in a hurry and failed to destroy some of their documents. In those documents, there were reports and suggestions by Zohrab, Talaat claimed, were treasonous. Talaat had added that had he known about these documents, he would not have sent Zohrab to Dikranagerd but would have him hanged in Byazid square in Istanbul and that he would have personally pulled the rope. In this case, Talaat did not hide his origin. In Ottoman Turkey, the hangman’s job was reserved for the gypsies

We have irrefutable proof to conclude that the Turks were thirsty for Krikor Zohrab and his compatriots’ blood and had unanimously voted in the Ittihad center on a plan for their annihilation much in advance. The rest was merely theatrics.

*****

The Death of Krikor Zohrab and its reporting in Ottoman Archives (excerpts from historian Taner Akcam’s book titled “Killing Orders”.

“The prominent Armenian parliamentarian, deputy for Istanbul, Krikor Zohrab, was arrested in Istanbul on 2 June 1915. He was sent off to the southeast Anatolian city Diyarbakir on the pretext of standing trial for charges filed in the military tribunal there, but was murdered en route near Urfa on July 19, his head being bashed in with a rock. At the moment that Zohrab was being killed, official documents were already being prepared reporting his demise from a heart attack. According to a report dated 20 July 1915, signed by the Urfa municipality physician, Zohrab experienced chest pain while in Urfa and underwent treatment there. After being treated Zohrab once again was sent on his way to Diyarbakir but was later reported to have died en route. The doctor traveled to the place of the incident and documented the cause of death to be cardiac arrest.

Another report on the incident was ordered by the priest , Hayrabet, the son of Kurkci Vanis, a member of the clergy of the Armenian church in Urfa. In this report, which bears his own signature, the priest claims that Zohrab died as a result of heart attack and was buried in accordance with (his) religious traditions.. At the bottom of the report, there is a note certifying that it was the personal signature of Hayrabet, son of Vanis, the priests of the Urfa Armenian church, along with the official seal of the Ottoman authorities. We have a third document in hand that also indicates that Zohrab was not murdered but died as a result of accident. According to an Interior Ministry cable sent to Aleppo on 17 October 1915, it was confirmed through the investigation document number 516, dated 25 September 1915, that Zohrab perished as a result of mishap en route.”

Tamer Ackcam cites these, along with others, as examples of “fact creation” and developing a historical narrative