By Matheos Eblighatian

Translated by Vahe H. Apelian

Edited by: Jack Chelebian, M.D.

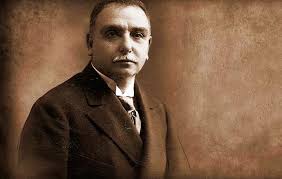

Instead of studying legal cases and preparing for superb defensive arguments, had he devoted to literature, the Armenian literature would have been much richer. However, his contribution to Armenian literature is such that he is regarded among the most famous Armenian writers. As a publicist, he penned valuable editorials with tight logic. I still remember his column titled (St. Gregory) “The Illuminator’s Broom”, which was reprinted at least a couple times per year by various publications.

Zohrab did not achieve immediate success as a lawyer. His activities in literature, editorials, and articles and his publication of the literary magazine “Massis” with H. Asadour got in the way. However, these initial years were not lost altogether. On one hand, his literary endeavors and on the other hand his successes at small or midsize legal cases reflected positively as his stature grew in Istanbul as well as in cities nearby.

Zohrab was no more the penniless person he had been. Instinctively he also gravitated towards social circles where women and having a good time were of the essence. His growing prominence in social circles, beyond the Armenian community as well, helped greatly his career in law.

When in 1903, I was able to stay in Istanbul and attend the School of Law, Zohrab had already attained fame as a lawyer. He did not shy away from displaying his wealth. He already had his family. They lived in a house across from the Luxemburg Café’. He had his spacious legal office consisting of a few rooms. He had such charisma that young students like me, who were studying law, would follow him earnestly. Not only I, but students from other races also followed him and attended his legal arguments during court proceedings. In Istanbul court, the proceedings took place from noon until 3 to 4 p.m. We did not have classes during this time and would walk around the hallways of the court waiting for an important case to attend.

During this time criminal and penal cases did not interest me. We rarely came across significant defensive arguments in such cases. Usually maritime and mercantile cases interested me the most. The French language predominated in court. Renowned German, Italian, British lawyers along with Zohrab, Stambolian, Ketabian, Yerganian displayed their legal rhetorical skills in eloquent defensive arguments which would last a half an hour, and sometimes even longer. The proceedings would adjourn for the prosecutor’s counter-argument to take place next time. At that time I was a novice in legal proceedings. I would tend to side with the last argument I heard only to find it dismantled, point by point, the next time.

I recall attending a big case. Attorney Rosenthal and another, whose name I do not remember, were dealing with a case that pertained to two hundred thousand gold coins for a railroad construction project through Hama. It appeared that Rosenthal was about to lose the case and thus had sought Zohrab’s legal assistance. Zohrab had prepared a powerful argument where his engineering knowledge had become a center point in structuring his defense. Zohrab’s argument had carried the day and assured Rosenthal winning the case for which he earned ten thousand gold coins and offered Zohrab only two thousand gold coins. Zohrab sued Rosenthal and demanded five thousand coins instead. The court sided with Zohrab. In another case, in a matter of fifteen days, Zohrab earned two thousand gold coins.

Zohrab was a hedonist. Right after his reimbursement, he frequented Boyukada with mixed company and after a week there, gave the remainder of his money to a troubadour. His wealth gave way to his extravagant spending on women and gambling. It was said that at times he would end up penniless when crossing the bridge from the island and at other times he would be laden with hundreds of gold coins having had success at the gambling table.

However, his indulgence in high life and his pursuit of women did not distract him from carrying the responsibilities of his legal practice professionally. One of Zohrab’s clients happened to be a beautiful European woman. Seeing her, his friend, attorney Diran Yerganian remarked to Zohrab whether she pays for his services with money or by offering her body. To which Zohrab immediately answered: “It would be shameful for me not to reimburse a woman for her services and it would be equally shameful for me to engage in my legal practice without being reimbursed financially.”

*****

I wrote at length about Zohrab’s increasing prominence socially and also professionally. His professional stature enabled him to establish friendship with many influential judges, which did not sit well with the Minister of Justice Germerzade Abdul Rehman Pasha.

Germerzade Abdul Rehman Pasha was the patriarch of a very prominent family and was an ex vizier. He was also the father-in-law of Sultan Abdul Hamid’s favorite daughter. He was not educated but he was very intelligent and surprisingly very decent and an honest man. He strived to keep the legal department on the right track. Sultan Abdul Hamid respected him a lot, that’s why no courtier or highly placed official dared to interfere with the proceedings of the legal department.

In spite of the Minister of Justice’s vigilance, the legal department was not altogether free from corruption. The Minister was very adamant and would right away dismiss corrupt lawyers or would hold them without promotion for years. In spite of the minister’s suspicion about Zohrab’s contacts with prominent judges, I remain convinced that Zohrab never engaged in corrupt practices. He was simply very effective and persuasive. Those who had not heard his powerful defense arguments, including the Minister of Justice, could very well have formed a wrong opinion about him. I would like to present two cases to make my point.

After graduation, most of the students of the law school would apply to the Minister of Education to be assigned to training posts in the courts. The assignment was for two students working together at a time. I had also applied. Almost a year later and after five weeks working in Hmayag Khosrofian’s law office as a secretary, I was informed that I was assigned to a post in Istanbul’s second penal court.

There was a heavy load in the courts. I, and my Turkish classmate, without stipends, went to the court every afternoon and alternately helped the recording secretary. When a lawyer presented his defense without resorting to a written text, we rapidly jotted down in shorthand his argument and afterward finalized it for record keeping. I was present when Krikor Zohrab presented his powerful arguments in two cases.

One day a handsome young man and his attorney Krikor Zohrab appeared in court to appeal the young man’s six months indictment issued by the court earlier in his absence. The young man had intimate relations with a young woman and subsequently refused to marry her. Both were Armenians and were well known in the community, especially the girl’s father, who was affluent.

Legally, an adult man and woman’s intimate relations were not the court’s business as long as they were consensual and were not against public morals. However, having an affair with a woman, after having promised to marry her but not keeping the promise was considered a legal matter, as long as there was tangible proof of the promise, such as letters. In this case, there were letters, which even contained references to the future, but there was no explicit promise of marrying. In short, the circumstances of the case were such that the verdict depended on the judge’s perspective and conscience; a situation that affords the defense lawyer maximum opportunity to display his analytical and persuasive skills. Zohrab was specially brilliant that day as he presented his argument in defense of the young man. The judges sided with Zohrab and exonerated the young man.

The second case was a far more important case that showed Zohrab’s skill as a lawyer. The case had to do with a commercial transaction in hundreds of thousands of gold coins between the French and the Ottoman governments. The proceedings took place in a special mixed tribunal because of Turkish Capitulation, which was grants made by successive Sultans to Christian nations, conferring upon them rights and privileges in favor of their subjects residing or trading in the Ottoman Empire. Consequently, the French Embassy had appointed two French judges out of the five judges. The rest were Ottoman subjects consisting of Osman Bey, another Turk and Stepan Karayan. Naturally, if the three Ottoman appointees voted unanimously, the government would carry the day.

Who among the three Ottoman appointees would vote against its government? In such tribunals, there had never been a case where the foreign judges voted against the interest of their citizenry. We studied the phenomenon of Turkish Capitulation as part of our course. It was rumored that the French Embassy had reached out to Stepan Karayan to vote on the side of the French judges, but he had refused to engage in such collusion. Thus the outcome of the trial depended entirely on the skill of the lawyer to convince one of the three Ottoman judges to vote along with the French judges for the French Government to win the case.

I was not present during the defense. Those who were present told me that Krikor Zohrab made such a powerful and irrefutable case that a miracle happened. Osman Bey voted in favor of the French judges forcing the Ottoman government to pay hundreds of thousands of gold coins. Nothing of that sort had happened before. Osman Bey was a just and honest man. He had represented the Ottoman government in the international court of justice in Lahey. He had an international reputation as a knowledgeable jurist. The Minister of Justice, fortunately, knew him personally only to reprimand him saying:

“Again that pig was able to bag us. Did you not have the same patriotic feelings as the giaour (infidel) judge?” The minister was alluding to Stepan Karayan.

The Minister of Justice did not dismiss Osman Bey but assigned him to a secondary post cutting his salary by one third.

The verdict was final, what remained was its implementation. To put an end to the Ottoman government’s procrastination, the French government resorted to dispatching its warship to show resolve in settling the matter for good.

The same week the Minister of Justice issued a circular barring Krikor Zohrab from practicing law in the Ottoman courts.