(remembering Serop Yeretsian)

Vahe H. Apelian.

Melkon

Gurdjian, who wrote under the pen name Hrant, is known among the Western

Armenian writers as the author who brought to light the plight of the Armenian

migrants from the interior of the country to Bolis, the Armenian word for

Constantinople.

Recently

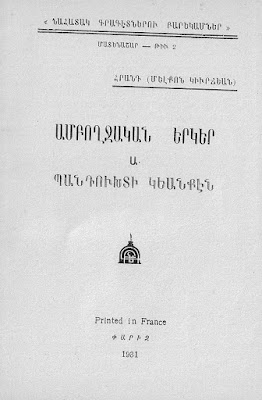

I read a book titled “Complete Literary Works” of Melkon Gurdjian. It is

subtitled “From Bantoukht's (Migrant’s) Life”. In Armenian it reads «ԱՄԲՈՂՋԱԿԱՆ ԵՐԿԵՐ», Ա. – “ՊԱՆԴՈՒԽՏԻ ԿԵԱՆՔԷՆ”. The

book is a compilation of letters Hrant wrote at the urging of his friend Arpiar

Arpiarian, who had these letters published in “Massis”, the journal he edited.

“Friends of Martyred Writers” published the book and noted the following in

their introduction of the author and his literary legacy noting that they are “glad

that the second volume of their sequel is devoted to Hrant’s letters about the

lives of migrants. These letters constitute one of the more memorable literary

works about the (Armenian) life in

the late 19th century.

According to Arpiar Arpiarian, Hrant is a bitter heart’s poet. His literary work depicts the inner pain

and distress of these souls that remained mostly unheard”.

The following are the

milestones of Melkon Gurdjian’s life.

1859. He was born in

the village of Havav in Palou, Western Armenia. He was brought to Constantinople

in his early adolescent years to continue his education. He graduated from the Üsküdar Lyceum (Djemaran). After which he

furthered his education. Henceforth devoted his life to teaching.

1888 – He started contributing

to literary journals “Arevelk”,

“Massis” and “Hairenik”, where he had his acclaimed writings about the

plight of the Armenian migrants posted under the header “letters from the lives

of migrants” signed by his pen name Hrant.

1893 – He got engaged

to the noted writer Krikor Odian’s niece. Not long after his engagement, he was

imprisoned for a month for suspicions of his political affiliation. He, in fact,

had become a member of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation.

1896 – During the pogroms

of Armenians in Bolis, government officials raided his house as well when he

was not at home, looking for guns but finding nothing of that sort, confiscated

and destroyed his writings. Fearing for his safety he fled for Varna, Bulgaria

where he established a school for the children of Armenian refugees fleeing

Turkey.

1898 – Contrary to

the advice of his wife and his friends, he returned to Constantinople where he

was apprehended and imprisoned for six months and later exiled to the interior

of country where he remained for the next ten years reporting to the police of

his daily whereabouts. During those years he gave private lessons for French to

medical students and medical doctors. He also wrote and translated including

“Life of Jesus” by the French philosopher and historian Joseph Ernest Renan. In

spite of his conforming and abiding by the dictates, he was imprisoned again

for two months and his writings were confiscated and destroyed once more.

1909 – He returned to

Constantinople after the establishment of a constitutional government in

Turkey, and resumed teaching of Armenian language and literature and classical

Armenian of which he was regarded an expert. He continued to contribute to

literary journals there, “Puzanteon” («Բիզանդիոն»),

“Azadamard” («Ազատամարտ») և “Yergounk” («Երկունք»).

1910 – He was elected

as a delegate and took part in the election of the Catholicos in Etchmiadzin.

Upon his return he published his impressions in a series of articles in

“Arevelk”.

1915 – He was also

apprehended in April along with the other Armenian intellectuals and community

leaders and was sent to the interior of the country where he was also killed.

Migration

continues to be inherent to the very fabric of the Armenian social life. I doubt

there is an Armenian who does not have a family history that does not include

migration. That aspect of our collective social life is so much engrained in

our psyche that we have coined a unique word for it in our lexicon, Bantoukht, well above the common word

used to describe migration and migrant in general. I know of no English word that can

possibly convey the sentiments the word Bantoukht conveys. It embodies

feelings the word migrant could not possibly express on its own. The word

amasses sentiments of being a foreigner, or a stranger in a distant land,

longing for the home and a way of life left behind and never contemplating

making the newly reality a home. No wonder that Hrant titled his

letters “Letters from Bantoukht” (Պանդուխտի Նամակներ).

Nowadays,

we often sentimentalize the Armenian life in our historic homeland. The

unfortunate and sad reality is that the conditions in the interior of the

country were mostly brutal to the point that the oppressed, mostly illiterate

and living in abject poverty, the Armenian subjects could not even eke out a hand to

mouth living forcing many to venture to Constantinople in the hope of saving

some money to send home. The migrants were overwhelmingly if not exclusively males,

and some as young as fourteen. Displaced, they lived in communal housings, Khans. They mostly congregated based on

the region they came from. It is

their plight that had catapulted the newly elected Patriarch Khrimian Hairig to take a stand against the National Constitution as ratified because it

deprived the interior of the country from adequate representation in the

National Assembly to have their grievances heard.

The

book I read is comprised of two parts. The first part is the collection of Melkon

Gurdjian’s writings in the form of the letters mostly addressed to Arpiar

Arpirian. These letters are masterfully written in an impeccable Western

Armenian and are highly expressive and moving. They are twenty in number. Each

letter depicts and describes mostly a heart-wrenching situation the migrants

and the families and parents they left behind experienced. It also depicts the

cherishable values the migrants harbored in spite of their harsh reality. Each

letter varies in length. The first letter posted in “Massis” is dated 1888 and

the 17th and last letter there is dated 1890. The next three letters

were posted in “Hairenik” and are dated 1891, 1892 and 1893 respectively.

The

second part of the book is titled

“Figures and Stories” (Պատկերներ եւ Վիմակներ). This section constitutes 9 chapters.

They are posted in “Hairenik” (1892(x3), 1893, 1895), “Massis” (1893) and in

“Azadamard” (1909, 1912, 1913).

In

these letters Hrant described the plight of these migrant workers noting that:

“At least one hundred thousand have been

cast away from their homes. Do you know who are they? They are those who would

have worked, toiled in the fields, harvested the crop. After sacrificing all

they can, they send home a meager saving.” He continued on noting that, “ It has been like this for centuries. The

tragedy continues today much like a worm that nibbles the lungs of the sick”

and alerts saying, “if the migration

continues like this, our inner provinces will be depopulated today or tomorrow;

know of this, it is a horrible truth”. A hundred and thirty years later, Hrant’s

warning remains compelling and rings a bell.

By

assembling Hrant’s writings from these various journals the members of the

association lived up to their names as true friends of martyred writers. Had

they not done so Hrant’s writings would have remained scattered in literary

journals long ceased from publication and would have been destined for oblivion.

We also would have been deprived of the true picture of a historic reality that

had plaqued the life of the Armenian subjects in the interior Turkey for generations.

Assembling his letters in a book, the “Friends of Martyred Writers” safeguarded

that historic reality and the literary legacy of this devoted martyred writer.

The

book is 218 pages long and measures 15x20 cm. The late Serop Yeretsian had

gifted this book to me. It is in soft cover but Serop had his copy bound in

hard cover. I post this piece in his memory.